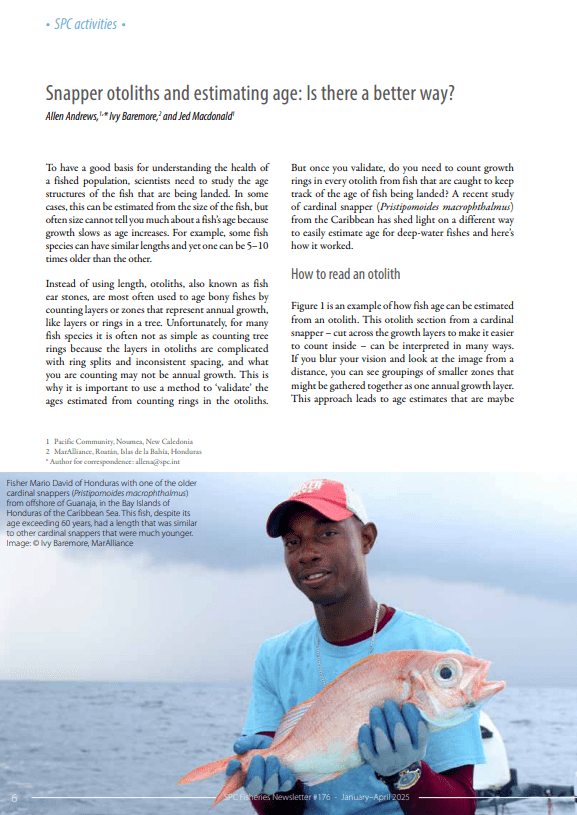

To have a good basis for understanding the health of a fished population, scientists need to study the age structures of the fish that are being landed. In some cases, this can be estimated from the size of the fish, but often size cannot tell you much about a fish’s age because growth slows as age increases. For example, some fish species can have similar lengths and yet one can be 5–10 times older than the other.

Instead of using length, otoliths, also known as fish ear stones, are most often used to age bony fishes by counting layers or zones that represent annual growth, like layers or rings in a tree. Unfortunately, for many fish species it is often not as simple as counting tree rings because the layers in otoliths are complicated with ring splits and inconsistent spacing, and what you are counting may not be annual growth. This is why it is important to use a method to ‘validate’ the ages estimated from counting rings in the otoliths.

But once you validate, do you need to count growth rings in every otolith from fish that are caught to keep track of the age of fish being landed? A recent study of cardinal snapper (Pristipomoides macrophthalmus) from the Caribbean has shed light on a different way to easily estimate age for deep-water fishes and here’s how it worked.