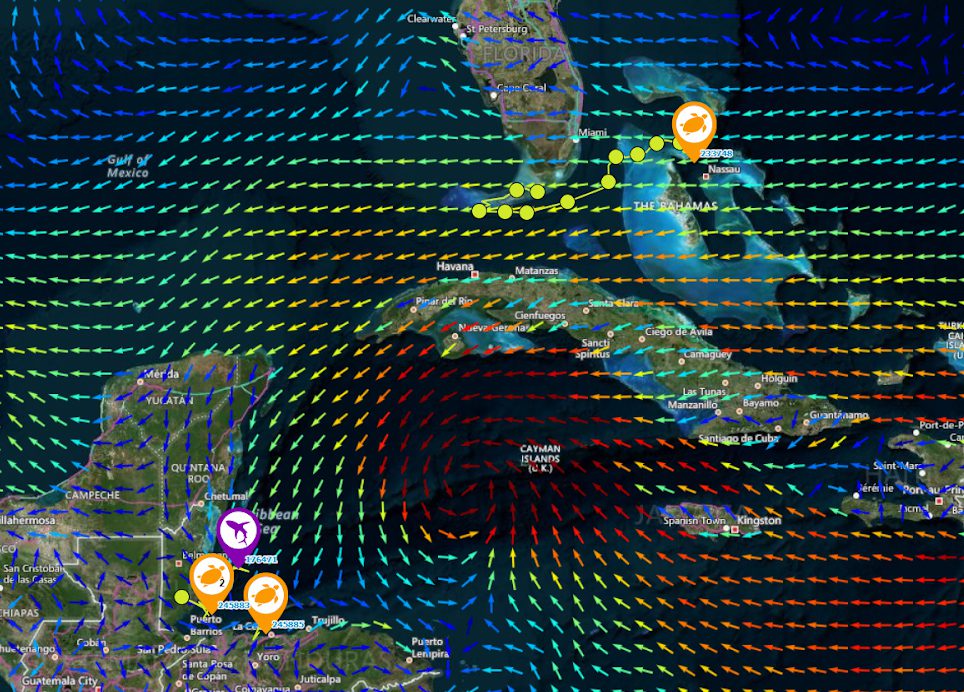

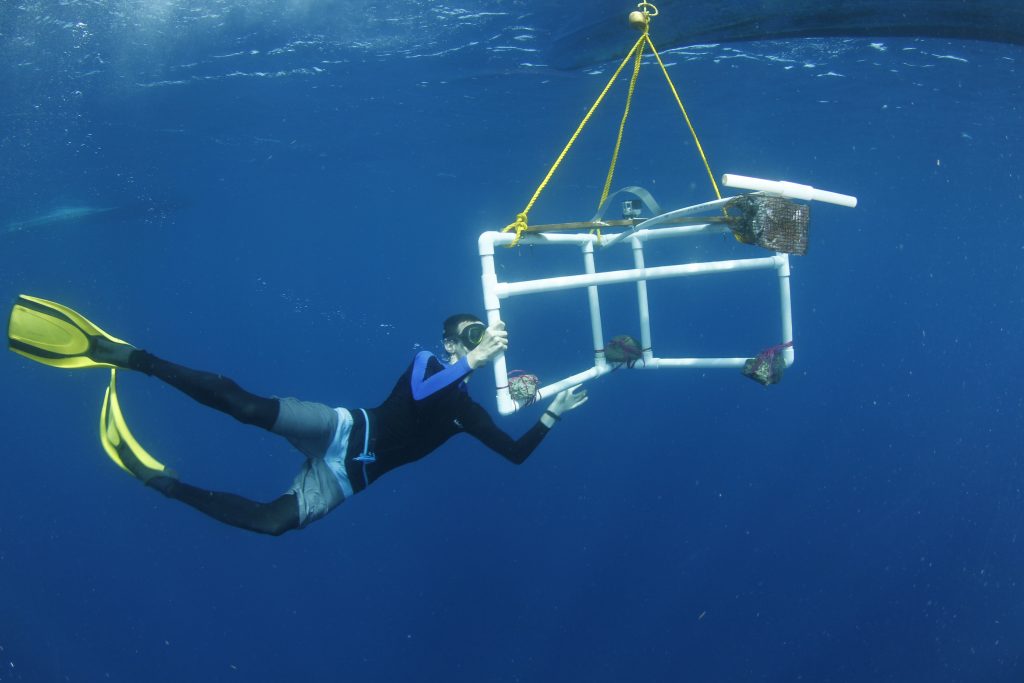

Significant gaps of information exist globally on sharks and rays, collectively known as elasmobranchs, and this is proving a challenge to conservation efforts. The MesoAmerican Reef region (Mexico, Belize, Guatemala and Honduras) is no exception. Honduras is one of 15 countries worldwide that declared its waters a “shark sanctuary”, which bans shark fishing and the commercialization of their meat and derivatives. Unfortunately, with limited enforcement and an unknowing public, shark fishing continues largely unabated in Honduras to date. To create the necessary baseline to identify changes in populations and inform the public about the large animals that ply their seas, we conducted the first large-scale marine megafauna monitoring project in the Caribbean of Honduras. The surveys monitor large animals (megafauna), including sharks and rays, and also sea turtles and big finfish (barracudas, snapper and groupers). Our methods are standardized, which allows us to compare results among countries and sites. We usually use three methods: Baited Remote Underwater Videos (BRUVs), in-water snorkel transects and scientific longlines. This year we were able to complete broad training in capture and release techniques with traditional fishers from several communities, and for the first time sharks were caught and tagged in Honduras!

Since many sharks are very long lived (think of the Greenland shark that reaches over 400 years old!) and like us humans take many years to reach sexual maturity, it will take several years of monitoring to determine if there are any changes occurring in the populations of these large animals. However, we can compare our results with other surveys throughout the region to get an idea of the health of Honduras’s marine megafauna. We are also already seeing some common trends, especially in Roatan. Greater abundance and diversity of finfish exist within protected areas with enforcement and more sightings of sharks in areas with less human activity – areas that actually do not necessarily coincide with protected area boundaries. This is not surprising, as studies have shown that sharks are most abundant in remote and little fished areas.

Although we did not catch as many sharks as we would have wished for on our scientific longline, our star capture was a juvenile tiger shark (Galeocerdo cuvier). This was an unexpected surprise, especially for our partner fishers, many of whom had never seen, let alone handled a tiger shark, a species often feared for its reputation as a voracious predator. Seeing the fishers’ enthusiasm and excitement for the capture and subsequently the release of an often feared animal gives us great hope that perceptions and behaviours can change in the shark’s favour. We can’t wait to expand this training and work to more communities and link the monitoring into our already popular Kids Meet Sharks program in Honduras.