For centuries, the ocean has been imagined as a place of silence. Divers will tell you it feels peaceful beneath the waves, a calm world where light fades and sound seems to vanish. Popular culture reinforces the image: serene blue expanses interrupted only by the songs of whales or the playful clicks of dolphins. But this is only half the story, beneath the surface, the ocean is alive with sound and, surprisingly, fish are active contributors.

The ocean is far from silent – in fact, we could say many fish are surprisingly “chatty”. Almost 990 species of bony fish (Osteichthyes) are known to actively produce sounds, from grunts and pops to complex calls. These acoustic signals can play a role in courtship, defending territory, coordinating movements, or simply maintaining contact with others in their group. Yet for most people, the idea of “talking fish” sounds like fiction.

These sounds often go unnoticed because humans cannot easily hear them underwater. Sound travels almost five times faster in water than in air, and many fish calls are outside the range or volume we can detect without special equipment. Marine mammals get more attention because their calls are louder and more easily recorded, but fish are constantly communicating too.

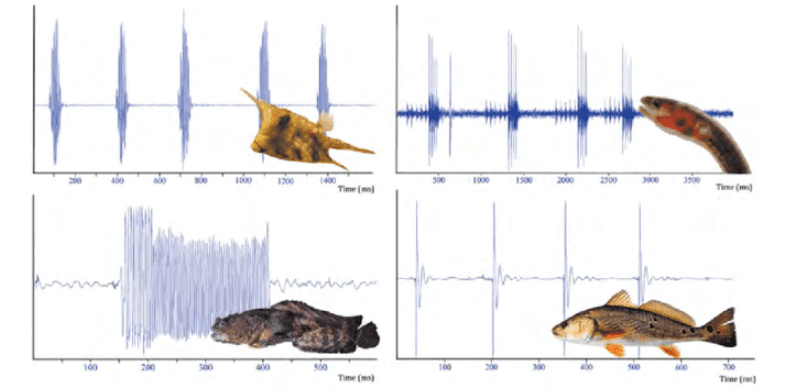

How do fish produce sound? Some use muscles to vibrate their swim bladders, sending low booms through the water. Others rub bony parts together in a process called stridulation, creating sharp clicks or rasps. The toadfish is well known for its “boatwhistle” mating call, while snappers and groupers – important species in the Mesoamerican Reef – emit grunts and knocks during spawning.

While less “vocal” than many fish, rays still contribute to the diversity of the marine acoustic environment and some produce purposeful sounds. Certain species of rays have been observed making rapid pulses or clicks when startled, possibly as alarm signals. Electric rays emit low‑frequency pulses as part of their hunting strategy to stun prey – signals that also register as sound in the water.

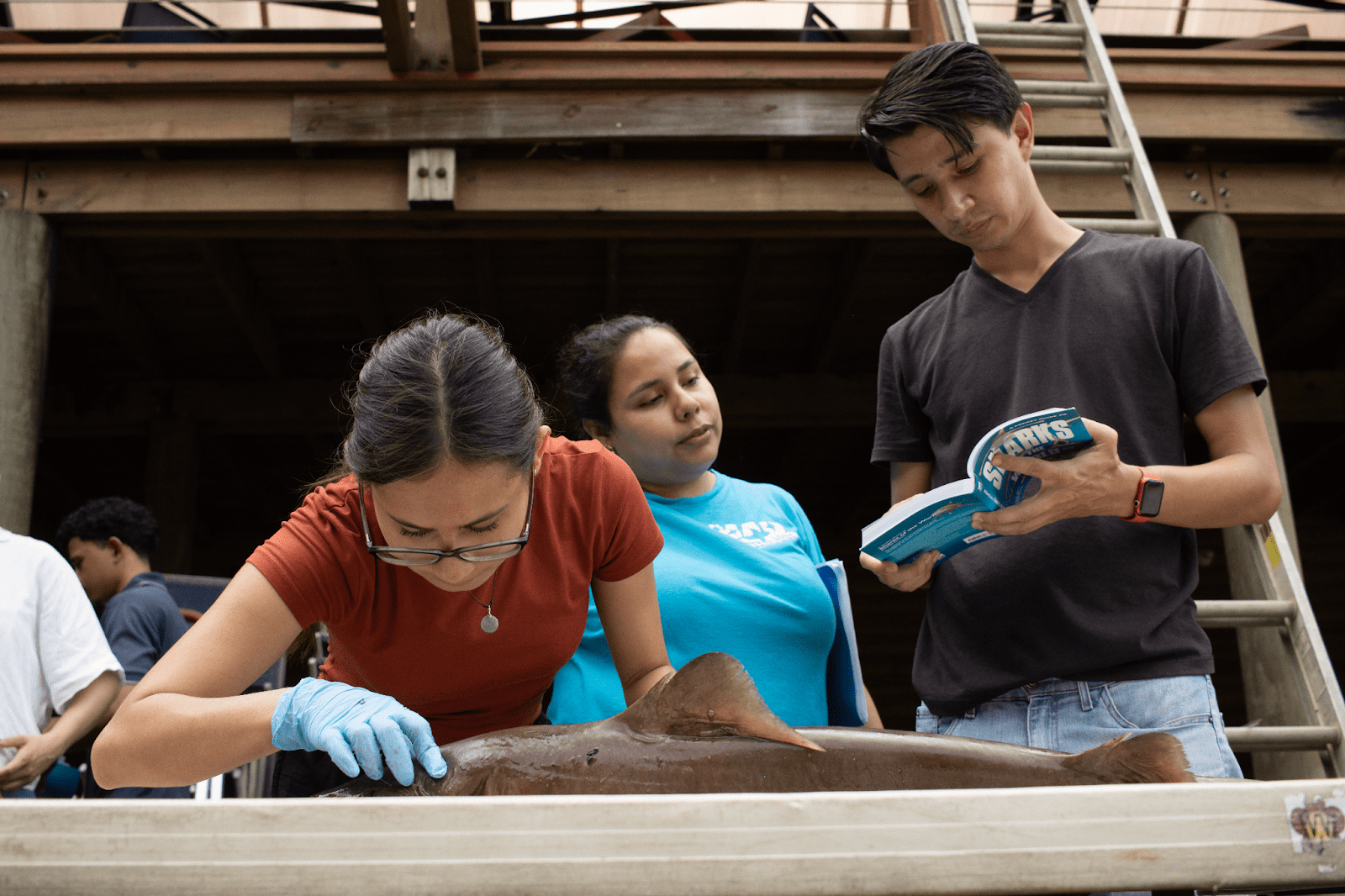

At MarAlliance, we are working to better understand this hidden language of the sea. In Belize, Honduras, and Panama, our teams collaborate with local fishers and community scientists to deploy small underwater recorders called AudioMoths. These devices capture the rich variety of sounds made by fish across habitats, such as mangroves. By analyzing these recordings, we can identify species, follow their seasonal patterns, and learn more about how they use their environment.

CC: Philip Christoph – Fetterplace et al. (2022). Evidence of sound production in wild stingrays. Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.3812

Every click, croak, or rumble adds to our understanding of fish behaviour and ecology. The sea has never been silent – it is, and always has been, a living symphony.