After seven years of scientific monitoring of critically endangered hawksbill turtles (Eretmochelys imbricata) at Coiba National Park, it is still unclear where are the main nesting sites of these cryptic animals are located. Although this may seem strange, it is to be expected since effective monitoring of sea turtle populations needs to be on the scale of decades, as a result of their longevity and late maturity (in the range of 20 to 30 years). For these long-lived species, long term monitoring is essential to observe trends and changes in their populations. In the case of a foraging (feeding) aggregations, individuals may spend 15 years or more in place before reaching sexual maturity and eventually migrating to their nesting grounds.

Photos by Gerardo Alvarez

Located off the western coast of Panama, Coiba National Park hosts the largest documented foraging aggregation of hawksbill turtles in the whole of the Eastern Pacific Ocean, and is the most important foraging ground for the Pacific population of this Critically Endangered species. This is in large part due to Coiba having the largest extension of coral reefs in the Eastern Tropical Pacific, but more importantly because it has been protected from fishing for over a century: Coiba was a penal colony for 80+ years, and no boats came near its coastline because of the potential risk of prisoners escaping. This odd form of protection permitted its coastal-marine ecosystems to thrive without the pervasive negative impacts of bottom trawls, gill nets, and other destructive fishing methods; in turn, this created favorable conditions to attract a myriad of marine biodiversity, including multiple sea turtle species.

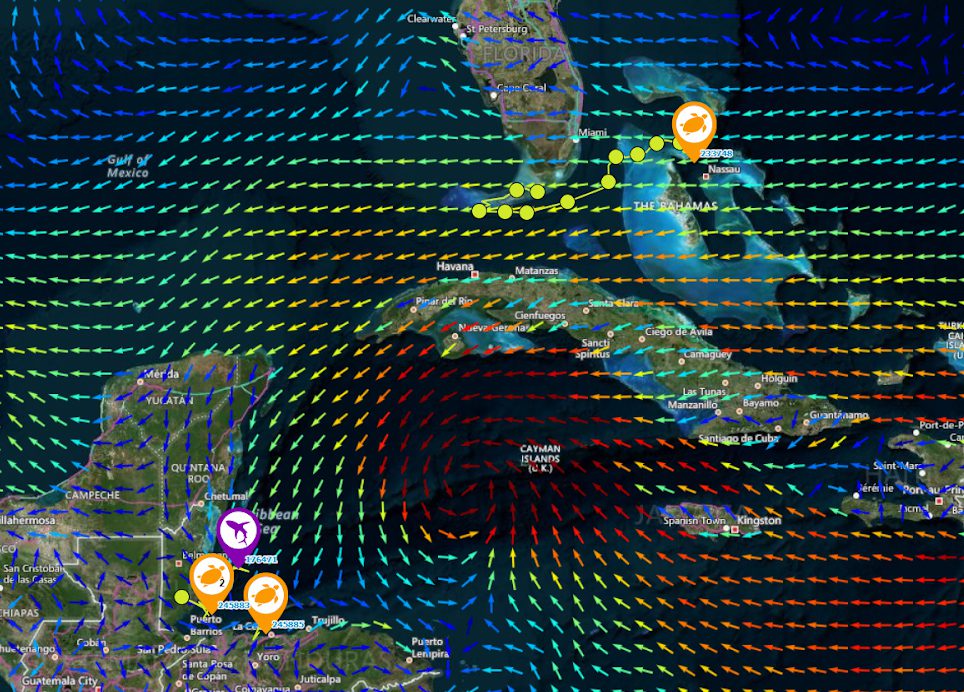

Coiba´s hawksbill population appears robust and healthy, with new individuals appearing every year. Incredibly enough, after seven years of biannual capture-mark-recapture studies, the proportion of newly captured individual turtles versus recaptures remains around 1:1, without showing signs of slowing down. In other words, for every 100 turtles captured, at least 50 are new individuals that have not been tagged, even after more than 600 individuals were captured and marked. Thanks to these tagging efforts, connectivity between the foraging grounds in Coiba and nesting beaches in the Azuero peninsula of Panama and Costa Rica´s Osa Peninsula have been found.

To date, no nesting by hawksbills have been observed within Coiba National Park, highlighting the importance of collaborative networks among those carrying out in-water research at foraging grounds and the various organizations working to protect nesting beaches, eggs and hatchlings. The Panatortugas network carry out much of the day-to-day (or night) groundwork here in Panama, while MiAmbiente´s DICOMAR are charged with the management and protection of these species and their critical habitats. Only through forging and fostering of these meaningful alliances can we guarantee proper conservation measures to ensure the survival for migrating marine megafauna and their key habitats.

Photo by Gerardo Alvarez

Photo by CC Rodrigro Donadi.

This work was possible due to a seven-year international research collaboration of multiple organizations, including Panama´s Ministry of the Environment, NOAA-NMFS, ICAPO, Fundación Eco-Mayto, CIMAD, among others; as well as a Research and Development grant from SENACYT.