People are remarkably fascinated by sharks. Whether they evoke fear, love, or pure curiosity, it is usually not very difficult to get people excited about sharks, especially kids. This has been clearly evident during our education and outreach events in Panama this year. Since the beginning of the year we’ve been able to engage the public with an educational booth at two large fairs, as well as talk to over 800 students and teachers from primary schools in Panama City. Besides teaching people about the incredible diversity of sharks and rays and sparking their curiosity about shark biology and anatomy, we also share the reality of unsustainable fisheries and what is happening to many of Panama’s sharks. And they are devastated.

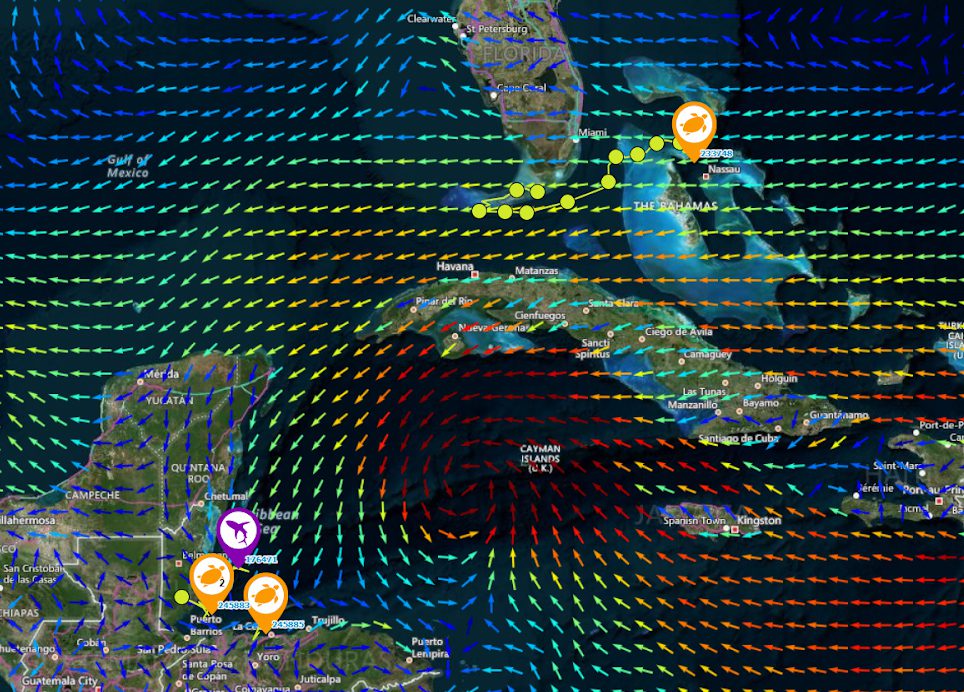

To meet the demand for more highly-prized fishes whose populations have drastically decreased in the last few years, it is not difficult to now find shark meat sold in fish markets and even supermarkets across the country. Ambiguously labeled as ‘cazón’, ‘corvinata’, ‘tollo’, or simply ‘pescado’ (fish) instead of ‘tiburón’ (shark), most of the public in Panama have no idea that the fish they are eating is actually shark meat. Hammerhead sharks are being hit particularly hard, as gillnets are used to catch large quantities of juveniles at coastal nursery sites along Panama’s Pacific coast. At the height of the reproductive season, when hammerheads migrate to Panama to give birth, a single boat may catch hundreds of newly born sharks in a day.

But what we’ve learned from our interactions with kids and the public at large in the last few months in Panama is that, once they know about sharks and their plight, people generally don’t want to eat them. Few of them know that there are hundreds of different species of sharks and rays inhabiting a variety of marine habitats around the world. Or that not every shark is a ‘white shark’ that wants to eat humans. Even fewer know that the meat from sharks and other large marine predators contains high levels of toxic methyl-mercury, or that it can take a hammerhead 10-15 years to reach reproductive age. Through these interactions we hope to not only change people’s perceptions of sharks (and inspire the next generation of marine biologists, divers, and ocean lovers), but arm them with knowledge so that they can make more informed decisions about what they consume that will ultimately make long-term positive changes for sharks.