Sharks are often portrayed as the ultimate rulers and top predators of our oceans. While it is true that some sharks are apex predators, this is not always the case. An apex predator is defined as an animal that exists at the top of any ecosystem’s food chain, meaning that they themselves have no predators. Sharks have evolved in our oceans for over 400 million years and take many shapes and sizes. In fact, there currently exist more than 500 species of sharks today, each of which plays an important and unique ecological role.

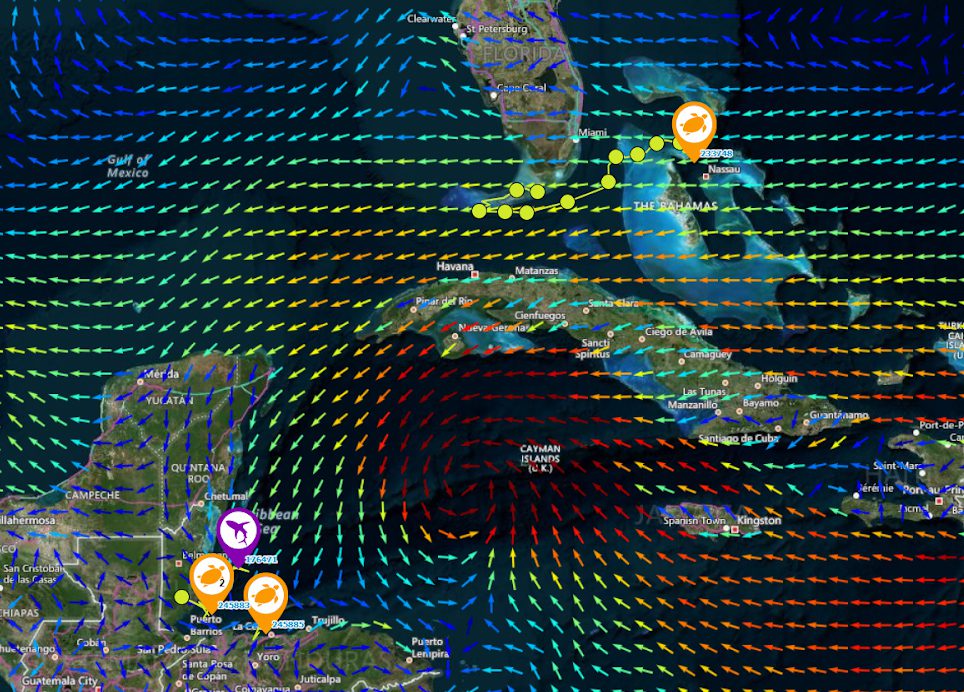

Take the whale shark, a gentle giant reaching up to 8.8 meters (62 feet), gracefully filter-feeding on zooplankton during open water migrations. On the other end, the lemon shark, at a more modest 3.4 meters (11 feet), thrives in the waters surrounding mangroves. As juveniles, the lemon shark sustains itself on shrimp and crabs but transitions to a diet rich in fish as they mature. The formidable (and unfortunately commonly feared) tiger shark, reaching up to 7.4 meters (25 feet), dominates reef ecosystems, feeding on a diverse range of animals from bony fish to birds, turtles, and mammals, but they are also known to scavenge. Some sharks even prey upon other sharks. Growing only to a humble 120 cm (4 ft), the small and nocturnal horned shark consumes the egg cases of the even smaller port jackson shark, whose length maxes out at a mere 70 to 90 cm (27 – 35 in). These examples underscore the extensive variety in shark species concerning size, distribution, and diet.

Even if a species of shark plays the role of the apex predator in an ecosystem as an adult, that does not mean that it is always on top. Like all living creatures, sharks progress through life stages, facing vulnerability during their early phases. Small species of sharks and the juveniles of larger species are vulnerable to predators such as large fish, crocodiles and other sharks. The diet of most sharks also changes as they grow and become faster and more efficient at hunting.

The ecological role filled by sharks is not only influenced by the specific species of shark and their life stage but is also dependent on the presence of other animals in the area. For example, great white sharks have long been apex predators in the coastal waters of South Africa where they come to feed on an abundant seal population. However, in 2009, orcas entered the area and soon became top dogs, preying on white sharks – specifically their livers. Soon thereafter, white sharks cleared the area, and scientists suggested it was to avoid predation by orcas. A few years later, large sevengill sharks appeared to replace the great whites, but the orcas returned and killed the sevengill sharks as well. These occurrences in the waters of South Africa demonstrate the dynamic nature of ecosystem food webs and the way a hunter can very quickly become the hunted.

So, are all sharks apex predators? No! Sharks fill all sorts of interesting and important ecological niches.