Over the past year, the internet was awash with stories of wildlife moving into urban areas and reoccupying sites where they had rarely or ever been seen previously. This led us to wonder whether marine wildlife in our study countries had caught a similar break from humans due to our Covid-mediated restrictions on travel and gatherings. In many tropical countries, coastal fishing was curtailed for several months as governments grappled with the uncertainties of contagion and the virus’ lethality, doing their best to balance restrictions while avoiding food insecurity and economic collapse.

During a period that mostly stretched from mid-March to early June 2020, traditional fishers were not allowed to go to sea in several countries where we work, such as Cabo Verde, Honduras, Belize and Panama. In many cases they were also not provided with any alternatives to feed their families or pay their rent and bills. Although a relative drop in the bucket of need, thanks to many supporters, we were able to support 22 fishing families for up to 5 months during the most challenging period, but as there were thousands of fishers across these sites, another set of questions begged: how have sharks and other fish fared following a short absence of fishing pressures? Would we be able to discern a Covid respite effect on any of the long-lived species that we study? Are marine protected areas proving effective for the protection of large marine wildlife as determined by our long term study on the differences in abundance, diversity and distribution between protected and unprotected areas?

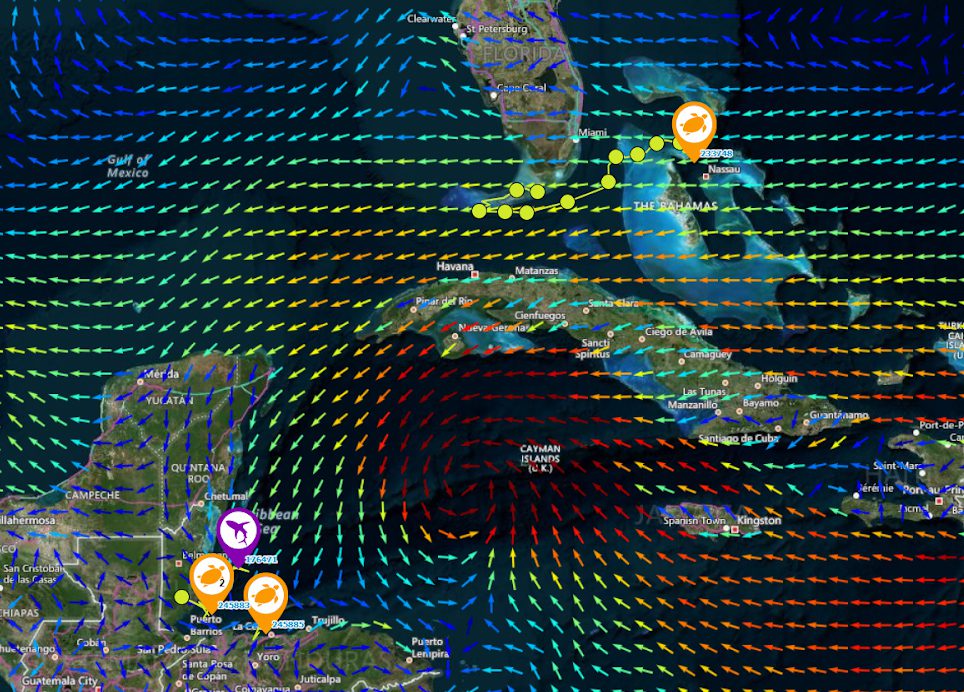

To answer these questions, we are once again setting about to monitor the status of sharks and rays and other large marine wildlife with our traditional fisher partners. Between April and June our team will be at work across multiple sites along the MesoAmerican Reef (which encompasses the countries of Mexico, Belize, Guatemala and Honduras) and in September in Panama, using our standardized tripartite methodology of underwater visual census transects, underwater videos, and scientific capture of sharks. Although we couldn’t travel to the field in 2020, we are fortunate we can count on a baseline dataset from previous years and added to in 2019 (the last time we were able to undertake monitoring), to which we can compare and quantify changes in animal numbers and distribution across sites.

One of the key sites we are studying closely is the Turneffe Atoll in Belize. Situated 32 km from Belize city, the atoll spans 1,317 km2 of coral reefs, mangroves, seagrass meadows and cayes. Declared a marine protected area (MPA) in 2012, the atoll is co-managed by the Turneffe Atoll Sustainability Association and the Belize Fisheries Department. Management and enforcement started in 2014, bringing about an atoll-wide ban on the use of nets and longlines similar to that enforced in other MPAs in Belize.

That same year, we were able to create a baseline for marine megafauna that has since served as a comparison and indicator of change for the subsequent years of monitoring. Our hope is that management of the fishing around the atoll will help the populations of threatened species found in the MPA, such as the scalloped hammerhead and hawksbill turtle, rebound over time. As we return to Turneffe this month, we hope to see positive changes in the number of stingrays, nurse sharks, Caribbean reef sharks, and other iconic species that are commonly sighted along other Belizean reefs.

We are trying to educate stakeholders on setting expectations for MPA effectiveness as one must consider the life history of the species that the MPA is expected to protect. Because many of the species we work with are long lived (30+ years for species of groupers and even snappers, longer for sharks and turtles), reach maturity at a late age (over 5 years for certain groupers and snappers, 15 years for nurse sharks), and bear relatively few young that survive to adulthood, long term monitoring needs to be conducted over decades to identify an MPA effect with rebounding populations.

As MPAs are now considered by most scientists as an essential tool for marine habitats and wildlife management and conservation, considerable work will be needed to boost MPA management and effectiveness at most established sites, ensure the continuity of standardized and locally-led monitoring, and establish long term financing measures that are resilient to external shocks such as Covid. Our localized approach to monitoring and building local capacities, especially in the age of Covid, is paying dividends in this sector, as work can continue and further provide traditional fishers with an alternative source of income to fishing. This is especially important with the globally set goal of protecting 30% of the seas by 2030 was set by the IUCN at the World Conservation Congress in 2016. As of 2020 only 5% of the world’s oceans was under true MPA management per the Marine Conservation Institute’s conservative estimates.

There is clearly much work to do to attain management and coverage goals, and we look forward to contributing our highly replicable and locally mediated monitoring efforts as a key part of the MPA puzzle and to assessing if indeed Covid gave sharks a break with greater survival recorded throughout our monitoring sites. And we are grateful to contribute to this effort this year in multiple locations thanks to the support of our fabulous individual donors, the MAR Fund, the Oak Foundation, the Whitley Fund for Nature, the Wildlife Conservation Network and the Pew Marine Fellowship