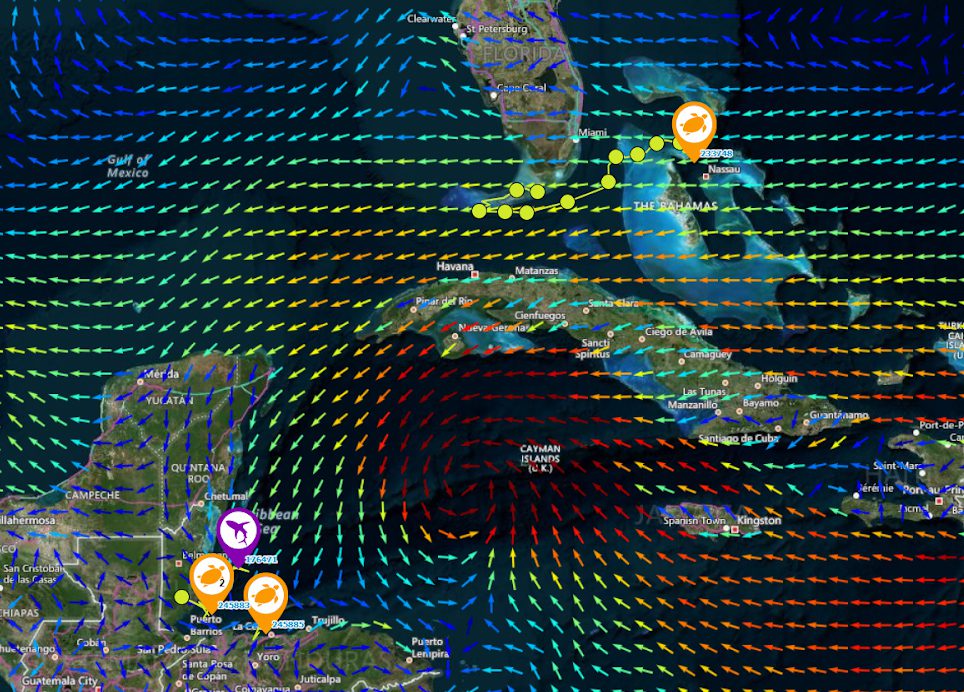

Community based conservation is all about relationships and flexibility. And trust and connections take years to build. We have blazed into a 3rd year of working with fishers, students, and communities in the autonomous indigenous Guna Yala Comarca on Panama’s Caribbean coast.

Our work shifted and expanded from our original goal of developing local capacities for controlling lionfish populations into a holistic program encompassing fisheries assessments, experiential education, capacity-building and addressing issues of food security and management measures.

Although many of the education events and workshops that we carry out in the archipelago still include training on the safe handling and use of invasive lionfish, we are developing a deeper understanding of the state of fisheries and fish populations in relation to community needs and challenges. This incremental knowledge has been made possible through our annual standardized monitoring of big fish, and the first fisheries-dependent assessment of fisheries and fishers in Guna Yala conducted since the 1980s.

Carried out by our Guna Research Officer and University of Panama student, Leyson Navarro, who visited 11 fishing communities throughout the 370+ km length of the Comarca. Leyson interviewed 112 artisanal fishers about their fishing habits, key species captured, perceptions of the fisheries and changes in local fish populations, and conservation mechanisms such as Marine Protected Areas and gear limits.

Fishers interviewed highlighted significant changes in fish populations over time- with fewer total fish and smaller individuals being caught now compared to decades prior. Some species that were once fairly common, such as tarpon and even sawfish, have not been seen since the 1980s.

This has supported the data we have gathered through our monitoring- with few big fish species observed overall, especially in sites close to human communities. Over 75% of the fishers interviewed said that fishing was their only source of income, and they supported an average of five dependents. While most fishers fish to feed their families, those living closer to tourist hotspots are driven to use unsustainable gear types such as nets to better supply the visitors’ burgeoning demand for seafood.

Though the majority of individuals were in favor of limiting or banning the use of nets, they were not in favor of creating protected areas or closing areas to fishing. Unfortunately, the only way to bring back the fish and its concomitant fishery is to reduce fishing effort. Insights derived from the fisher interviews will underpin meetings to be held with the newly elected local leadership as they define novel strategies to move fisheries towards sustainability and secure food security in the Comarca.