An increasing number of studies are revealing that fish are far older than we ever thought. You may ask why this important: sound management of a fishery requires a good understanding of how quickly (or slowly) individual fish in a species grow, at what age they begin to reproduce, and how long they live. These factors represent some of the most basic biological information required to understand the status of a population and or species, because we need to ensure that enough fish are able to replace themselves before they are removed from the sea. A study that seeks to answer these questions is known as an age and growth study. As great variability in growth occurs across populations and within a same species, age and growth studies should be conducted for every distinct population of a species that is subject to fisheries.

Before an age and growth study can be conducted, we need to figure out how to age the fish. How do we do that? Well, as fish grow, seasonal variation in temperatures cause differences in growth rates, with fish growing more quickly when the water is warmer and food more abundant than during the cooler months. These differences in seasonal growth form annual ‘bands’ in calcified structures within fishes’ bodies, and otoliths are one such type of structure. Otoliths are mineralized structures located in the fish’s inner ear, which enable accurate sensing of body orientation to gravity. By carefully extracting the pair of otoliths from two capsules near the top of a fish’s head, we hold the key to the life history of that individual fish. In order to view the annual bands, and therefore age the fish, a variety of methods may by used, but most involve cutting these delicate structures in half through the center, and counting the bands using a microscope. The fish’s age is then linked to its weight, length, sex and reproductive condition at the time of capture. Once we’ve collected otoliths from hundreds of fish, these data will not only give us the growth rates and ages at maturity for the population, but can indicate important factors such as natural mortality and the species overall risk of over-exploitation by fisheries. Determining the age of fish is a tedious but relatively simple process, and the growth rate of a fish’s body has been found to be generally proportional to the temperature of their environment.

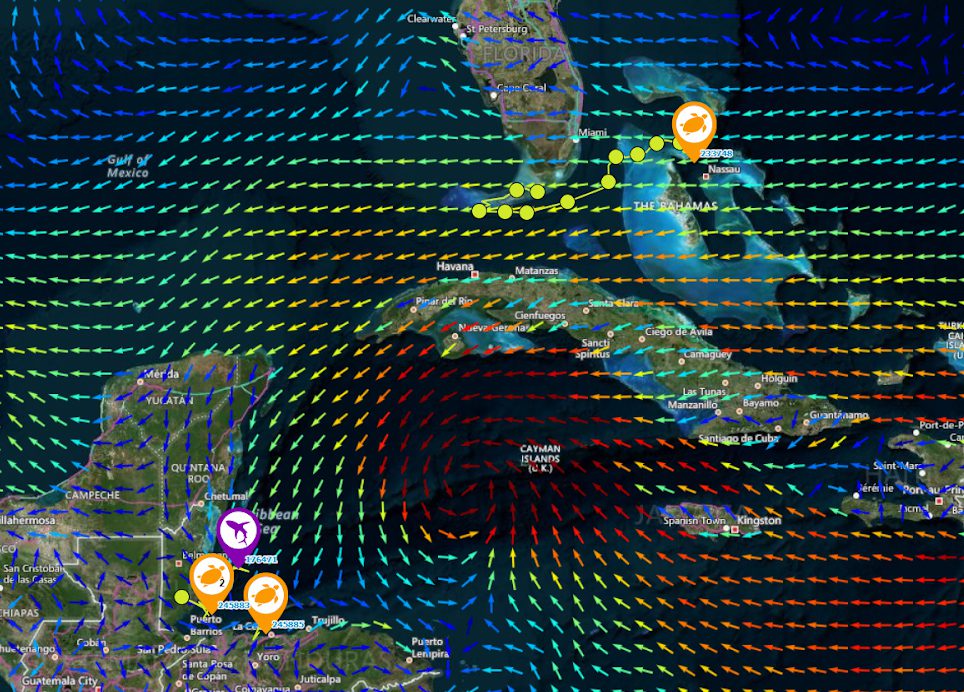

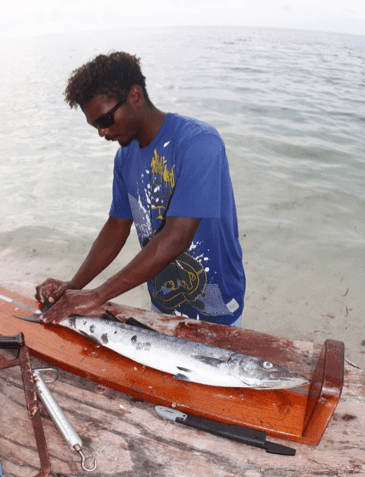

A remarkably recognizable and yet poorly studied species that we frequently encounter during our fieldwork is the great barracuda (Sphyraena barracuda). This charismatic, predatory fish species can often exceed 1 meter (3.3 ft) in length, and in fact can grow as large as 1.8m (5.94ft)! Popular as a food and sport fish, great barracuda are often targeted by fishers throughout the tropics, and surprisingly the fishery is currently unmanaged throughout most of its range. Equally surprising is the lack of scientific studies on this important species. In order to remedy this glaring deficit, we have collected measurements and samples from 290 great barracuda throughout the primary reefs of the MesoAmerican Reef (Mexico, Belize and Honduras), to create the needed age and growth study for this species.

Our study will significantly improve understanding of how great barracuda age and grow, and will provide important information in the development of local, national and regional management strategies for this commonly captured fish. Already we are finding that the fish we see are older than we expected, with barracuda of moderate size easily reaching 19 years of age. This gives us something to think about when assessing whether the populations of a fish we consider common can withstand the increasing fishing effort recorded worldwide.