Ivan the loving logger

“Over there…OMG it’s a huge logger…wait, there are two loggers!” I yelled out to my teammates as we hauled ourselves into our boat from the calm seas, after looking for over two hours for loggerhead turtles. In fact, we were keen to find any other type of turtle that would lend itself to capture for our in-water study of turtle behavior at Belize’s Lighthouse Reef Atoll. Everyone followed my pointed finger to see, 75 m away, not one but two loggerheads on the surface, locked in a happy embrace (well maybe happy for the male on top, less so for the female whose head kept getting pushed underwater).

There was no hesitation from Ivan Torres, a traditional fisher from Belize’s northern fishing community of Sarteneja. He grabbed his fins, donned his round glass plated mask and with a huge smile and glint in his eye, slipped smoothly into the water. With the stealth of a jaguar, he swam out of the turtle’s view and popped up behind the amorous couple, rapidly grabbing the top and bottom of the male loggerhead’s carapace (shell) and angling it towards the surface to stymie any attempts to swim downwards. The single-handed capture was unbelievable.

We didn’t quite realize how special it was until we saw the size of the animal as we angled our boat next to Ivan and the turtle, which by the way seemed none too happy that he had been caught in flagrante. We carefully lifted the hefty chelonian gentleman into the boat and prepared to take him back to Half Moon Caye for measuring and tagging before releasing him back at the site where he was caught.

We are specifically catching and tagging loggerhead turtles in-water, with a strong bias on male turtles. This will help us better understand the geographic preferences of this highly threatened species in relation to protected areas, threats from poaching, boat traffic, pollution, and coastal development. Elucidating these questions for male turtles is particularly important, as once hatched and at sea, they do not return to beaches to nest. The majority of information held on turtle spatial ecology is focused on nesting females. Yet, as global temperatures rise, hotter nesting beaches are causing egg-bound turtle embryos to develop into females at a disproportionate rate, greatly skewing the ratio of females to males. We are therefore concerned that male turtles may soon become even more scarce and endangered than their female counterparts, limiting reproduction and the future survival of the species.

But back to our turtle. To keep the ginormous chelonian gentleman calm, we covered his eyes with a damp towel, and all took turns massaging his very broad and muscular neck – a handy trick I learned from a colleague working with loggers in the Gulf of Mexico. It took six of us to move him from the boat to a quiet, shady spot on the caye’s sandy shore. His weight very likely surpassed 325 pounds. To keep him safe, we created a wooden slat corral around him to minimize movement and treated him to a full turtle spa treatment with cool water poured over him, continued eye covering and massaging while we measured his curved carapace length. He remained quiet while we prepared the upper shell’s scutes for the placement of a satellite tag.

This was very likely the first time he had been ashore since he left the nest as a hatchling. And based on his carapace length, we estimated him to be over 70 years old. When he was born, Winston Churchill and Truman were in power, the Korean War was raging, Belize was still a British colony (British Honduras). A little sanding cleaned off the algae to leave the beautiful, variegated shell dry and ready for the two-part epoxy that would hold the tag that would hopefully transmit his location for over two years, every time he came to the surface to breathe (about every 20-30 minutes or so).

After a period of curing, the epoxy holding the tag was cured and we were ready to apply an alphanumeric tag to each flipper. Two are placed on the posterior edge of each flipper in case one is lost, and all numbers are added to a central database for tagged turtles run by the Belize National Turtle Working Group, integrating a range of non-profits including MarAlliance and government institutions. If a turtle is recaptured, the tag(s) is read, the turtle is remeasured to check growth, and the distance moved from the original tagging point is assessed.

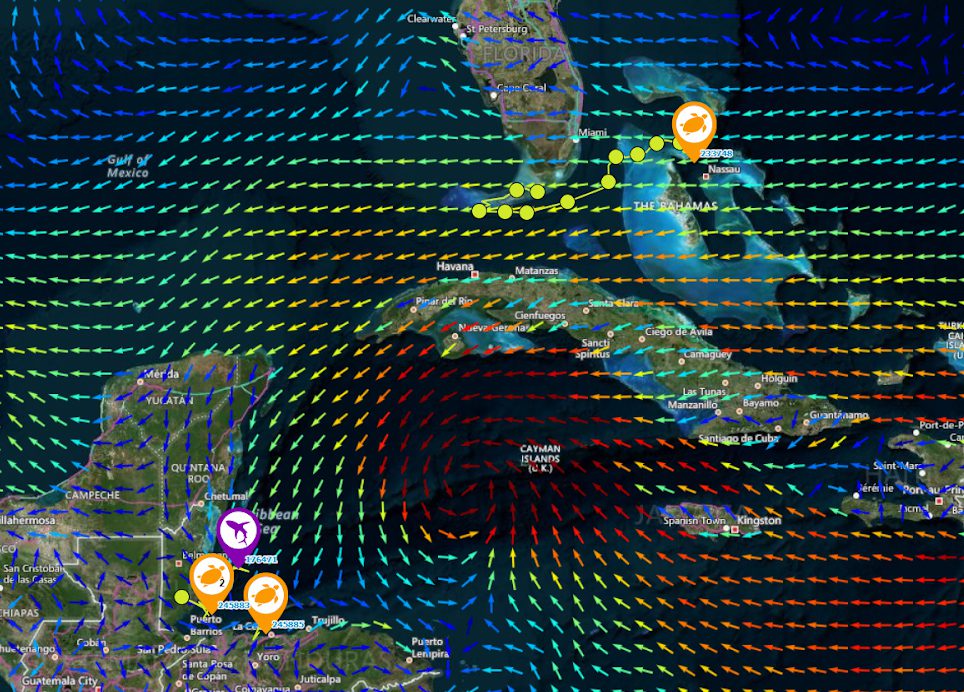

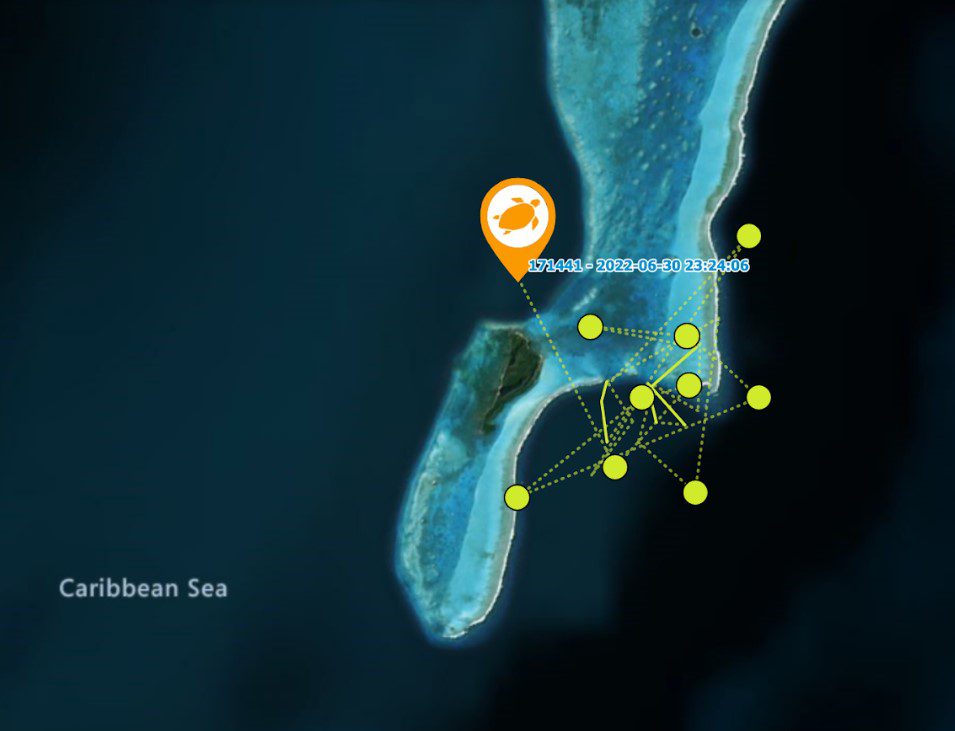

Taking our large logger back to his original site of capture for release was a smooth affair. With the help of 4-5 people inside the boat, we gently lifted him over the side of the boat, being careful to avoid the large claws on the flippers that help him to grab on to female turtles while mating. As he slipped into the water, he swam away with his new satellite transmitting bling on his back to tell us what waters he prefers over the next two years. We all decided it was most fitting to name him Ivan, which made Ivan beam with pride, knowing that he both supported cutting-edge science and could now track “his” turtle for the coming months.

As we work to create a tracking page on our website, stay tuned to social media to see where Ivan goes over the coming months. You’ll be able to see our data in real-time as we find out whether the tracks of in-water captured male turtles differ considerably from those of females and whether their movements place them at risk from additional threats from poaching, boat traffic, or development.