Monitoring large, mobile and little known species requires a lot of work and dedication, and not a small amount of luck. We’ve all had days, and even weeks where we just can’t catch a break (or a shark), despite all factors – good weather, ideal location, great crew – being in our favor. And then there are the days that get us through the rough patches, where everything clicks and we get amazing results.

This past July we had a bit of both types of luck during the deep sea project: two long, hot days during which we caught absolutely nothing, followed by one single day in which we tagged and released nine sharks from three different species. The first two sharks we caught that morning were, ironically, night sharks (Carcharhinus signatus), which although considered primarily deep-dwelling (50-600 m), don’t have a lot of the characteristics we associate with deep-sea sharks, such as huge eyes, water-pumping spiracles on their heads, or light-emitting organs. Rather, they look quite similar to other “sharky sharks,” like the silky shark or even Caribbean reef sharks. In fact, they’re closely related to their shallower cousins, being in the same genus.

Until last year, we only had anecdotal evidence that night sharks even occurred in Belize, and most people thought they were brief seasonal visitors to one atoll in the south of the country. But as we learn more about this species we are finding that they likely occur throughout the country, and may be here year-round. We’ve now tagged and released eight night sharks, and have recorded a ninth on one of our deep Baited Remote Underwater Videos (BRUVs). It’s not a huge sample size, but it’s providing some important data for this understudied species.

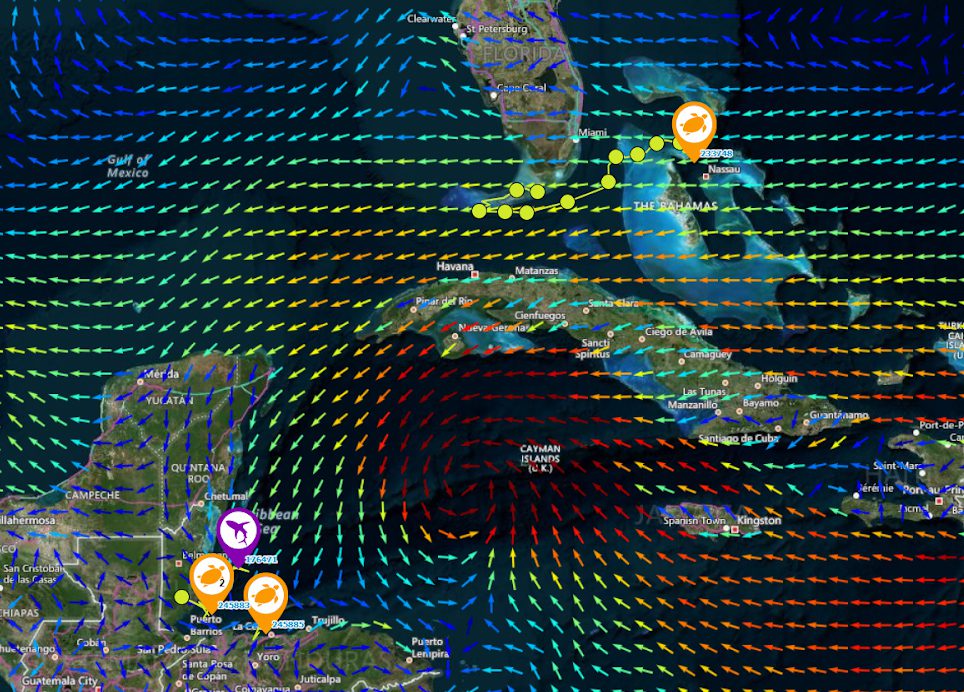

Tagging highly migratory sharks with conventional tags – those that do not communicate with satellites or receivers – is largely an exercise in futility. After all, many species of sharks can cross ocean basins in just a few weeks, and often tags are not reported by fishers, as many assume they will get in trouble if it is a protected or special species. So we were more than a little surprised to get a message earlier in October that one of our conventional tags had been recovered in Cuba. A quick search for the tag number in our database revealed that it was one of the night sharks we had tagged just two months earlier!

Although we are thrilled to have this information, this exciting finding is tempered by the implications of its capture. While it was reportedly released, this shows that at least 12% of the night sharks we tagged have interacted with fishing gear. Given what we know about low reporting rates, the number of night sharks being captured in the region is likely very high. Night sharks are listed as Vulnerable to Extinction by the IUCN Red List of Species (redlist.org), which is an organization that uses scientific and fishery information to evaluate the global status of species around the world. Once common in Caribbean fisheries, and especially Cuba, night sharks are now considered rare throughout the western Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean. Their Vulnerable status is a result of heavy and unregulated fishing of the species, especially around seamounts off Brazil.

These first records of night sharks in Belize show that this species likely traverses our waters throughout the year, and may even use Glover’s Reef as a mating aggregation. As most Belizean fishers do not target deep water sharks, they are fairly well protected while they are here, but increasing fishing in deep and pelagic waters, and especially in surrounding countries, will continue to threaten this highly migratory species. We don’t know where our night shark went after its presumed release in Cuba- was it to US waters where the species is fully protected, or did it loop to the south where it would encounter heavy fishing activity? How large is its range and how many fisheries is it exposed to as it migrates? These are just some of the questions about this and other vulnerable species we are starting to answer with this project.