Standing on the veranda of our Belize based office, we can readily see the Belize Barrier Reef with its jagged coral reef crest, and beyond this line of coral and waves, the open sea. What many people don’t realize is that the reef shelf drops rapidly from a shallow 15 meters to over 1,000 m depth within a stone’s throw of the reef, and this is literally mare incognita (or unknown seas).

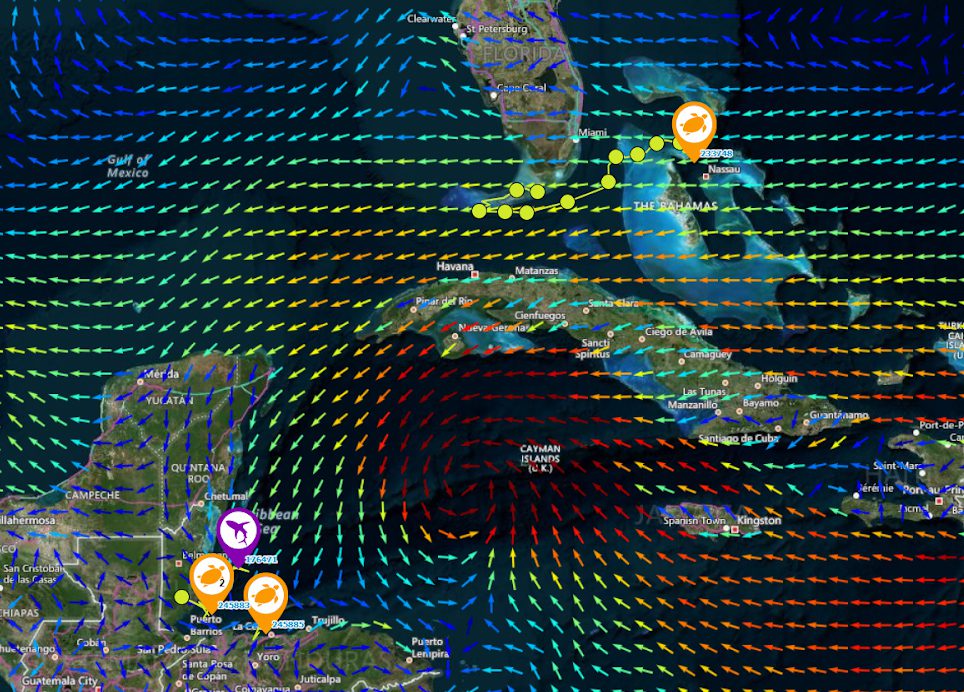

This proximity to deep waters and ease of access becomes highly relevant to fisheries management as near-shore coastal fish and fisheries are declining globally, and fishers are increasingly moving into the deeper waters in a bid to maintain their catch and meet the rising demand for seafood. Yet the deep sea environment is very little known throughout the world, and especially in the western Caribbean. Despite our lack of knowledge of this ecosystem, fisheries continue to develop in the deep sea. In the MesoAmerican Reef Region (MAR), almost nothing is known about the species that inhabit the waters deeper than 150 m (500 feet). In fact, we don’t even have a full catalogue of the deep-sea shark species that are in the MAR. To counter this paucity of data, MarAlliance is currently conducting research on the species that inhabit the deeper waters of the MAR to determine which species inhabit this region and which might be vulnerable to overexploitation from fishing.

Deep-sea sharks are remarkably well adapted to their environments, with many possessing large eyes, specialized teeth, and spiracles for pumping water over their gills in low oxygen environments. Upon capture, these sharks undergo a bit of a shock, moving from up to 500 m (1,200 ft) to the surface in under five minutes: not only are they exposed to extreme light conditions, but undergo a change in temperature from as little as 11°C (52°F) to 29°C (84°F).

We knew from other researchers’ studies that many deep sea sharks have extremely fatty livers and are therefore more buoyant than their coastal counterparts. Because of this, some species may have a difficult time swimming back down to depth after they are brought to the surface. We found that while smoothhound and night sharks swim rapidly back to the deep quickly after release, the bigeye sixgill sharks make a more meandering descent. Gulper sharks appear to have the hardest time, being both extremely buoyant and rather sluggish.

So we aim to get them back into the deep as quickly as possible. Using a method commonly applied to finfish that we discovered also works well with sharks: a lead weight with a barbless hook attached to a line takes the shark down to depth very quickly. After a few trials, we feel like we have nearly perfected our technique, which we were able to use to successfully release a gulper shark on our last sampling trip.

As we have expanded our deep-sea shark research project in the MesoAmerican region, while working with the handful of traditional deep sea fishers to teach them monitoring techniques, we have also added to the number of species we are encountering. We now have a catalogue of seven species, a list that we are adding to with every major expedition we make. The deep is a new frontier that is both threatened by expanding fisheries, but also represents a region of new discoveries that keep us on our scientific toes.