Like it or not, the international trade of shark and ray products is a world-wide industry. Countries that plan to export shark meat, fins, or other products are required to abide by international laws that are intended to protect species that are in danger of extinction. In some cases, a country may want to sell products from a species that is globally endangered, but abundant and well-managed within the exporting country. This is where CITES steps in.

The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) is a multilateral treaty to protect endangered plants and animals. States that agree to voluntarily adhere to CITES agreements are known as Parties. All imports and exports of species covered by the CITES Convention have to be authorized through a licensing system. And CITES is the only convention overseeing wildlife that has teeth, meaning that Parties that break CITES conventions are subject to compliance measures, including trade suspensions.

Species that fall under CITES regulations are ‘listed’ under one of three appendices. Rules are strictest for species listed under Appendix I that are threatened with extinction, such as sawfishes. These species are only traded in exceptional circumstances, and cannot be commercialized. Species on Appendix II are not necessarily threatened with extinction at the moment, but their trade must be monitored and regulated to ensure the survival of the species. Species on Appendix III are protected in at least one country, which has requested assistance from other Parties in controlling trade.

If a Party wants to export products from a CITES listed species, they must first prove that the species was legally obtained, and that trading it will not cause detriment to the survival of the species. Even scientists have to abide by these laws, and must obtain CITES permits for exporting and importing scientific samples taken from listed species.

So how does a country or Party prove that a CITES Appendix II or III species can be sustainably exported? With the support of the CITES authorities, the Party completes a Non Detriment Finding (NDF). NDFs help Parties to consolidate all the information on the biology, threats, management, and population status of the species in order to determine if the export of the species products falls within CITES rules and meets the criteria for species persistence. In the past, this has been accomplished manually with oodles of paperwork and reference manuals, and was often a long and exhausting experience. In 2019, with support from the German government, MarAlliance enabled the streamlining of the process by creating an automated template that the end users could modify themselves. Colleagues from Blue Resources Trust, an NGO based in Sri Lanka, built upon the template to produce a user-friendly online tool, reducing the time needed to complete an NDF. The template is tailored specifically for sharks and rays and their particular life histories, and has already been successfully adopted and implemented by several countries.

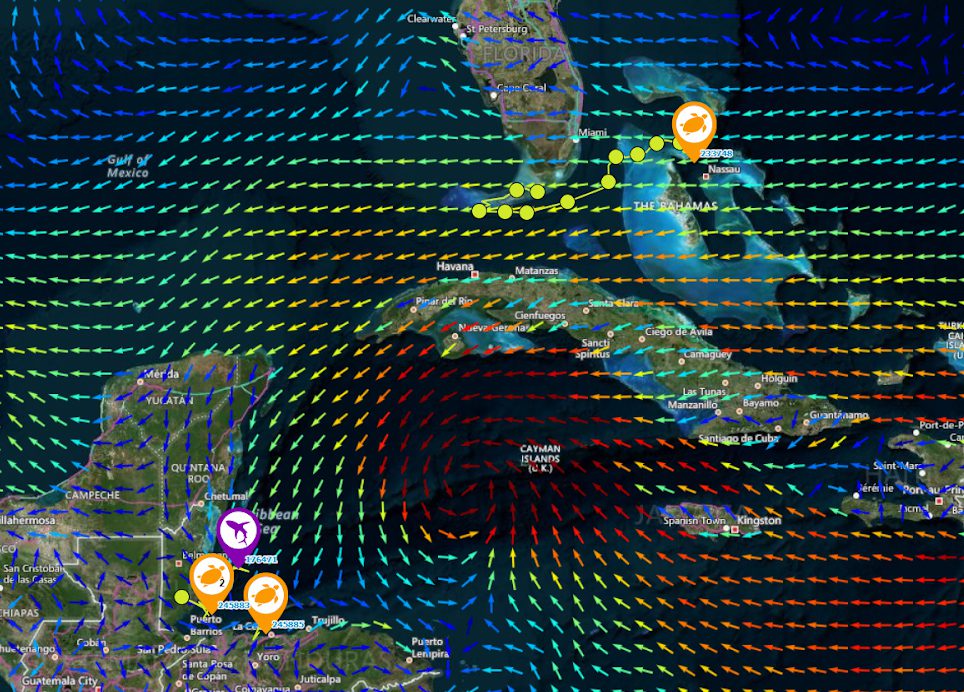

In exciting news, Belize conducted its first NDF for sharks last week, and three species were considered: the great hammerhead, scalloped hammerhead, and silky shark (all Appendix II). A team of fisheries and MPA managers, CITES authorities, and scientists collaborated to determine whether hammerhead and silky sharks landed by fishers in Belize can be sustainably exported. As founding members of the Belize National Shark Working group, proponents of NDFs over a decade ago, and co-creator of the e-NDF tool, we were thrilled to help lead this process, which will position Belize well for the CITES Conference of the Parties meeting planned for November 2022 in Panama.

With newly enacted regulations banning gillnets and extended protection zones for sharks in and around Belize’s three atolls, bycatch of sharks, and especially hammerhead sharks, is expected to decline. By undertaking the NDF process, Belize is setting itself up to further ensure the sustainability and hopefully rewilding of sharks in its territorial waters. We look forward to sharing the results of the NDF in the coming months, and are excited to work with our colleagues toward an outcome that will support the rebuilding of populations of these iconic species for generations to come.